SEATTLE — This summer’s 50th anniversary of Ray’s Boathouse prompted co-owner Douglas Zellers to toast Ste. Michelle Wine Estates by carefully pulling corks on some rare bottles, starting with the first red wine it ever released — a 1967 Pinot Noir.

“A few years ago, with the anniversary coming up, I knew I wanted to do something retro,” Zellers said. “I thought about tasting wine that was most likely on our menu in the 70s, and it has taken me a few years to gather these from the secondary market.”

Last week, Zellers carved out several hours to share these special bottles with Tyler Alden, the Master Sommelier who is the director of food and beverage at Willows Lodge in Woodinville; and three members from the Ste. Michelle Wine Estates team — Brian Mackey, head red winemaker for Chateau Ste. Michelle; certified sommelier Lauren King, senior manager of wine education for Ste. Michelle Wine Estates, and Erik Harshfield, field sales manager for Ste. Michelle Wine Estates and a graduate of Central Washington University’s Global Wine Studies program. The panel also included Chris Nishiwaki, WineBusiness.com contributor, and Ray’s wine director Darrell Statema. Alex Tilden of Ray’s Boathouse facilitated the tasting.

The opportunity to experience a bit of history that involved the late André Tchelistcheff — the famed Napa Valley winemaker who consulted on Ste. Michelle’s first wines — enchanted Zellers.

“The first half of this tasting is Tchelistcheff,” Zellers said. “He had a hand in these because he was coming to Washington starting in 1967, so his thumbprint is on that Pinot Noir and some of these others.

“And to think they were sending these out the door for $4.75, according to one of the hand-written stickers on the bottle,” Zellers added with a chuckle. “Amazing.”

Ray’s Boathouse, Cold Creek Vineyard Began In ’73

When Ray’s Boathouse began in 1973, Tchelistcheff was still very much involved with Ste. Michelle. In fact, Cold Creek Vineyard — first planted in 1973 — is dedicated to “The Maestro” with a sign at its entrance. Tchelistcheff, known by some as “the founding father of the Washington wine industry,” inspired his nephew Alex Golitzin to launch now-iconic Quilceda Creek north of Seattle.

“Back when Ray’s started, all of the menus were done with a Smith-Corona typewriter, but those menus and lists were thrown away,” Zeller says. “I don’t even have pictures of them. So what could have been on a wine menu when we started in ‘73? Lancers. Blue Nun, right? Some sort of sweet Riesling and probably these Ste. Michelle wines, I’ll bet you.”

This spring, Ray’s Boathouse, Café and Catering will begin offering throwback apparel in conjunction with the Friday, June 23 celebration and kickoff of what’s expected to be a hopping summer season.

“We’ve got a lot of unique, old photos that are pretty cool,” says Zellers, who began managing Ray’s in 2013 after spending seven years as food and beverage director at the Washington Athletic Club in between management roles at Northwest wine-minded Wild Ginger and Landry’s affiliate Palisade.

And while there’s plenty of history surrounding Ray’s, including a long and storied connection with the late Julia Child, the restaurant remains very much front of mind throughout Seattle. The year before the pandemic, viewers of KING-TV voted Ray’s as the Best of Date Night restaurant in Western Washington.

Last year, Zellers, executive chef Kevin Murray and their team showed haven’t lost a step as Ray’s Boathouse was voted by readers of Seattle Magazine as the Best Restaurant in 2022.

An Afternoon Of Comets Over ‘Shooting Stars’

However, this day along the shore of Shilshole Bay was a Washington wine time machine project. Zellers expected some “shooting stars,” but a few came with a longer tail than expected.

“It starts when you pull the capsule off to see what the cork is like — whether it leaked or not will tell you something,” Zellers says. “Very rarely are these old Washington wines garbage. I’ve had some sour wines, but other than that, they either show really well and then fall apart or they take some time to get going — especially the old David Lake wines from Columbia (Winery). A lot of the time, if you come back to the wine in a half hour it’s absolutely amazing. They just need time to do their thing.”

And the opportunity to taste history prompted a quick look at the outline of the early days of Ste. Michelle Wine Estates.

In 1967, longtime winery executive Vic Allison of American Wine Growers launched Ste. Michelle Vineyards as a brand focused on vinifera. The first four releases featured varietal bottlings of Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinot Noir, Sémillon and a rosé from Grenache.

That same year, the company asked Tchelistcheff to serve as a consultant to Ste. Michelle’s first winemaker — Howard Somers. Sources for that inaugural vintage included Yakima Valley sites Hahn Hill north of Grandview and a nondescript planting near Benton City known as Vineyard 7.

The influence of Tchelistcheff included the Russian’s 1974 recruitment of winemaker Joel Klein to Ste. Michelle. Klein’s résumé included Simi Winery — where Tchelistcheff also was involved. Klein’s father-in-law, the late Harold Berg, an Oregon native and acclaimed professor of winemaking at UC-Davis, also encouraged him to take a job in Washington. Klein left in 1983 to join grower/vintner David Wyckoff in their launch of Snoqualmie Vineyards, a brand Ste. Michelle purchased in 1991.

Other figures behind some of these bottles included Kay Simon and homegrown winemaker Cheryl Barber Jones, a graduate of Richland High School and Washington State University’s food science program. Last month’s sold-out First Ladies of Washington Wine event included an image of Tchelistcheff sitting in a lab alongside Barber Jones. In 1983, Barber Jones replaced Klein as Ste. Michelle’s head winemaker.

The Lack Of Malolactic Fermentation

In 2017, Great Northwest Wine co-founder Andy Perdue orchestrated a similar library tasting that included the 1967 Cabernet Sauvignon. Keys to that Cab’s enduring framework included the influence of Tchelistcheff as well as the absence of malolactic fermentation — a winemaking method to develop mouthfeel in red wine that was not yet used in the Washington wine industry. Klein has been credited as the guideline light in Washington for malolactic fermentation.

Albert Coke Roth, III, longtime legal counsel for Great Northwest Wine LLC, has been a member of the Pacific Northwest wine industry his entire adult life, beginning with his family’s multi-generation distribution business in the Columbia Basin. A decade ago, during his days as a columnist, Roth wrote about the influence of Klein.

“The first few Northwest Cabs that I consumed came from Associated Vintners, the daddy of Columbia Winery, and Château Ste. Michelle, and the wines they made in the late 1960s and early 1970s were acidic, tannic, and horribly vegetative,” Roth wrote. “It was not until 1974 when Cabernet Sauvignon actually became drinkable out of the Northwest after Château Ste. Michelle hired Joel Klein fresh out of the University of California-Davis, as their winemaker.

“Joel had a specialty; malolactic bacteria,” Roth continued. “Most people don’t brag about being best pals with bacteria. Joel did. One reason the wines had such blistering acidity before Joel came to town was because their chemistry did not allow for the softening effects of a secondary acid-reducing fermentation. Joel proudly told me the story about starting the malolactic culture in a bottle, gently pouring it into a warmed five-gallon carboy, then a week later lowering the fizzing carboy into a large tank of Cabernet where the miracle occurred, yielding the Château Ste. Michelle 1974 Cabernet Sauvignon. Thanks, Joel.”

That 1974 Cab wasn’t a part of this Ray’s retrospective. Surprisingly, the shining star of this special tasting proved to be the 1973 Cabernet Sauvignon — grapes harvested prior to the arrival of Klein.

A Look At Bottles From 1967 To 1979

Ste. Michelle Vineyards 1967 French Oak Pinot Noir, Washington State: Understandably, it was no longer a “red wine” in terms of its wardrobe, looking more like an Arnold Palmer in the glass with its Earl Grey tea appearance. And the nose leaned toward sherry. Still, there were enough notes of sea air and dried brown fruit — think of cherry fruit leather and prune juice — joined by a surprising delivery of acidity to provide enough reward. (12% alc.)

Historical note: It is likely this was the first varietal red vinifera wine — ahead of Cabernet Sauvignon — released by Ste. Michelle Vineyards. And Corti Brothers, the acclaimed wine-savvy grocer in Sacramento, Calif., featured all four single-variety bottlings from the 1967 vintage, according to The Wine Project by Seattle author/winemaker Ron Irvine.

Ste. Michelle Vineyards 1970 Cabernet Sauvignon, American: The back label clearly stated that it was Cabernet Sauvignon grown in the Yakima Valley. Its appearance was reminiscent of Dr Pepper, and aromas of bottle bouquet included some complexity with slate, beef bouillon and red fruit leather. The panel quickly noted some depth of fruit on the palate with dried plum and red currant, a nibble of celery leaf and joined by a remarkable grip of tannin. (12% alc.)

Historical note: The label on the shoulder of the bottle included the following phrase — “U.S. REPRESENTATIVE VINTAGE 1970 VINTAGE” and it prompted a snicker as it conjured up thoughts that it was a Congressional wine. The bottle also included a reference to the Texas warehouse for Bon-Vin, Inc., the first national distributor for Ste. Michelle. (New York native Charles Finkel, who founded Bon-Vin, would sell the company four years later to U.S. Tobacco Co., and become Chateau Ste. Michelle’s first VP of sales.)

Ste. Michelle Vineyards 1973 Cabernet Sauvignon, Washington State: As Tyler Alden, MS, quickly noted, “This wine has held onto its hue,” which proved to be a harbinger. There was a remarkable abundance of dark brambleberries in the nose and across the palate, joined by black cherry skins and cranberry acidity, a combination that created lots of texture. And it was no shooting star. About an hour after it had been opened and poured — yet not decanted — the nose still offered compelling notes of blueberry and pomegranate. Bottom line, those who have cared for this bottle can pull the cork on a helluva 50-year-old wine. The back label packed a surprising amount of the chemistry, including the Brix (23.2) and pH (3.2) at harvest (Oct. 17). “After fermenting for approximately 9 days, the free run wines at 12.7% alcohol and .76% total acid were used exclusively and then aged in American and French oak barrels.” (12% alc.)

Historical note: National interest in this wine would have received a boost because Ste. Michelle’s 1972 Riesling topped an October 1974 blind tasting staged by the Los Angeles Times. Also in 1974, Seattle businessman Wally Opdycke and his group — after just two years of purchasing the company and a year after establishing Cold Creek Vineyard — sold Ste. Michelle Vintners to U.S. Tobacco Co. It stands as the most important transaction in the history of the Pacific Northwest wine industry.

Chateau Ste. Michelle 1975 Cabernet Sauvignon, Washington State: The Klein Era would be in full force with this wine, but time was not kind to this bottle. Its color mirrored the 1970 Cab, and the fluid held a scant amount of charm. The nose was short and reminiscent of Worcestershire sauce. While the structure was decent, the fruit was gone. This front label features the chateau that opened prior to the 1976 harvest. The back label referenced “our spectacular new Chateau near picturesque Woodinville,” an October harvest at an average 25.5 Brix, malolactic fermentation, pH of 3.45, TA of 0.65 and American oak barrels. Apparently, no French wood. (12% alc.)

Historical note from 1975: Considering that it was planted in 1973, it’s likely that third-leaf fruit from Cold Creek Vineyard factored into this bottling and the remainder of the lineup opened this day at Ray’s.

Chateau Ste. Michelle 1976 Merlot, Washington State: Disappointment in the ’75 Cab was soon forgotten with this brief shift to Merlot — the first bottling of the variety by Ste. Michelle. In retrospect, this might have been the most expressive red wine of the afternoon. There was minerality, dried blueberry and chocolate-covered pomegranate in the nose. Inside, there was more delicious blue fruit, and the panel’s descriptors included raspberry yogurt, which hit on the buttercream found on the midpalate and signaled the involvement of malolactic fermentation. According to the label, harvest began Oct. 14 at an average of 23.2 Brix at a pH of 3.35 and TA of .67. Again, it was barreled in American rather than French oak. (12% alc.)

Historical note from 1976: Ste. Michelle opened the doors in September 1976 to the $6 million “chateau” that U.S. Tobacco built on the estate that once served as the home of timber baron Frederick Stimson.

Chateau Ste. Michelle 1976 Cabernet Sauvignon, Washington State: The first bottle suffered from cork taint. The second bottle brought notes of cherry cola, dried blueberry, forest floor and menthol. On the palate, creamy red fruit on the entry led directly to frontal tannins that penetrated the top of the gum line, making for a lively and rather tasty wine. (12% alc.)

Historical note from 1976: Wine merchant Bob Betz began his storied career with Ste. Michelle, and the early duties of the future Master of Wine included creating memorable experiences for visitors to the new tasting room.

Chateau Ste. Michelle 1977 Cabernet Sauvignon, Washington State: In the glass, this wine provided perhaps the biggest roller coaster ride of the afternoon. And it fell off the rails at the start. The color reminded one taster of Geritol, and the nose prompted comments such as “dog kibble,” “asparagus” and “steamed bok choy” — a blend of vegetal characteristics and sulfur. There was some dried red fruit that came out as it sat in the glass, joined by leather, and an Old World finish included herbal and dried red currant notes. “It tastes better than it smells,” remarked one judge. (12% alc.)

Historical note from 1977: Klein hired Kay Simon as assistant winemaker. She had been making wine in the San Joaquin Valley after graduating from University of California-Davis. (Simon’s nephew, Brian Mackey, is in his second decade of working for Ste. Michelle. His uncle, Clay Mackey, is co-founder of Chinook Wines and married to Simon.)

Chateau Ste. Michelle 1978 Cabernet Sauvignon, Washington State: The cellar at Ste. Michelle might have needed a few space heaters during the fermentation of this wine because of the historically chilly winter of 78-79. Beyond that, however, this wine was solid, offering some elegance. But it was not stellar. Unlike the previous vintages, the back label did not include any technical information. It did continue to display the maps that show the similarities in latitude between the Columbia Valley and the heart of France. (12% alc.)

Historical note from 1978: This vintage marked the arrival of Wade Wolfe to Washington as Ste. Michelle recruited the Ph.D. from UC-Davis for viticulture expertise. (In 2012, now-defunct Wine Press Northwest Magazine named Thurston Wolfe Winery as its Pacific Northwest Winery of the Year.) It also signaled the first vineyard-designated effort with Cab from Cold Creek.

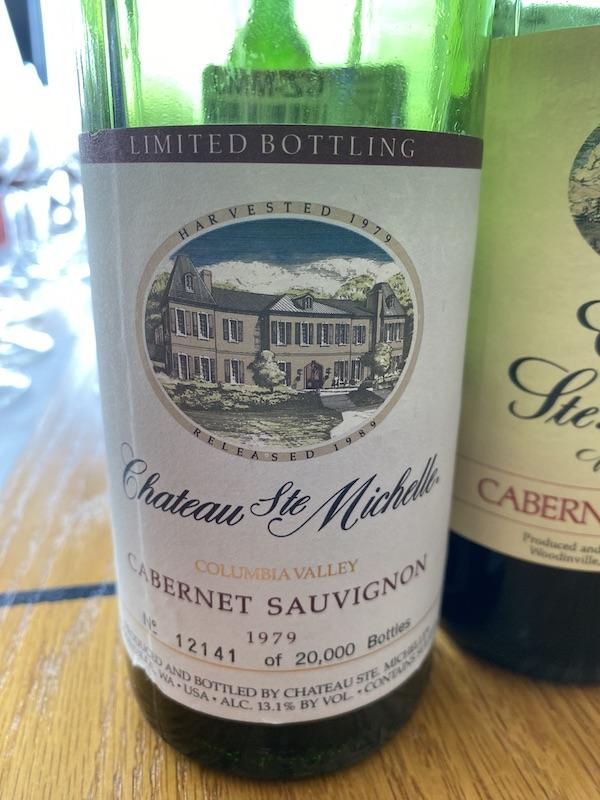

Chateau Ste. Michelle 1979 Limited Bottling Cabernet Sauvignon, Columbia Valley: This represents an unusual approach, and those of us who grew up in Eastern Washington during the late 1970s and experienced the ash from Mount St. Helens in 1980 won’t soon forget the aforementioned bitter winter of 1978-1979. It brought a long stretch of days when the temperature didn’t climb above minus-10 Fahrenheit, so this vintage and the diminished production level reflected the vine damage throughout the Columbia Valley. This nose is amazing with its Bing cherry, light toast, blackberry, sage and forest floor moss. Flavors of Chukar Cherry come with some crunchiness to the structure, which includes a surprising amount of oak and extraction. It’s still a bold Cab and has the bones for another 5-10 years. This was No. 12,141 out of the 20,000 bottles — approximately 1,700 cases — released in 1989. According to the label, that 1979 harvest began in September, and the grapes averaged 24.1 Brix, pH of 3.53 and TA of 0.73. (13.1% alc.)

Historical note from 1979: The use of “Columbia Valley” on the front label stands out. The first American Viticultural Area was established by the federal government in 1980, starting with the Augusta AVA in Missouri (Napa Valley was No. 2), and the Yakima Valley AVA was the first in the Northwest in 1983 — a year before the Columbia Valley AVA. … Clay Mackey was recruited from the Napa Valley by Ste. Michelle as a viticulturist during the 1979 harvest.

Insights By Ste. Michelle Winemaker, Master Somm

Brian Mackey said he came away from the afternoon wanting to dig more deeply into his company’s archives.

“The most surprising wine to me was the 1973 Cab,” the winemaker shared with the tasting group. “The tannin structure was still so robust and intense with fruit aromas and flavors that leapt out of the glass and lasted for over an hour without fading. It stood out from every other wine we tasted.”

Alden, who earned the title of Master Sommelier last year, marveled that such life still remains in these bottles.

“The fact that many still had enjoyable fruit notes in addition to the tertiary/age-related components was wonderful,” Alden noted. “The quality of wines were surprisingly robust for an industry in its youth, and the imprint of Washington terroir was clear.”

Alden ranked the ’73 Cab both as his favorite “for total presentation and arc in glass” and as his biggest surprise “because of how it had held itself together.“ He viewed the ’77 Cab as the “most unique expression,” pointing out that the “use of sulfur and its aging arc gave beautiful changing moments in the glass.”

As a winemaker, Mackey took special delight in the work by Klein and that team.

“My favorite series of wines were the 1976-1978 Cabs,” Mackey noted. “They represented to me an era of experimentation and change in style. There was a huge shift from 1973-1975, and there was even a gap to the 1979. I felt like I was witnessing in the glass a time I’ve heard so much about when the Washington wine industry was first starting to expand.”

And yet, the wine that held the most charm for Mackey was the ’79 Cab.

“We didn’t talk much about it because it seemed so modern and current compared to the others, but that is exactly what I liked about it,” Mackey said. “It was exciting for me to see fruit extraction, tannin structures and aromatics that I still see in the wines I’m making today — 44 years later.”